The emperor soon died, leaving no heir, so the two regent dowagers arranged for his cousin, aged three, to become the Guangxu emperor. When the young emperor contracted smallpox in late 1874, Cixi and Ci’an became regents once again. The emperor married when he was 16, and the regency was dissolved. The dowagers continued to govern, in the words of the official histories, by ‘listening from behind the screens’ of the throne room.

Cixi and Ci’an were the only remaining regents and Cixi herself was solely entrusted with the imperial seal that authenticated edicts issued from the court. A regency of six male officials along with the late emperor’s highest-ranking widow, Ci’an, and the new imperial mother, Cixi, was empanelled, but within months the officials were removed by imperial princes.

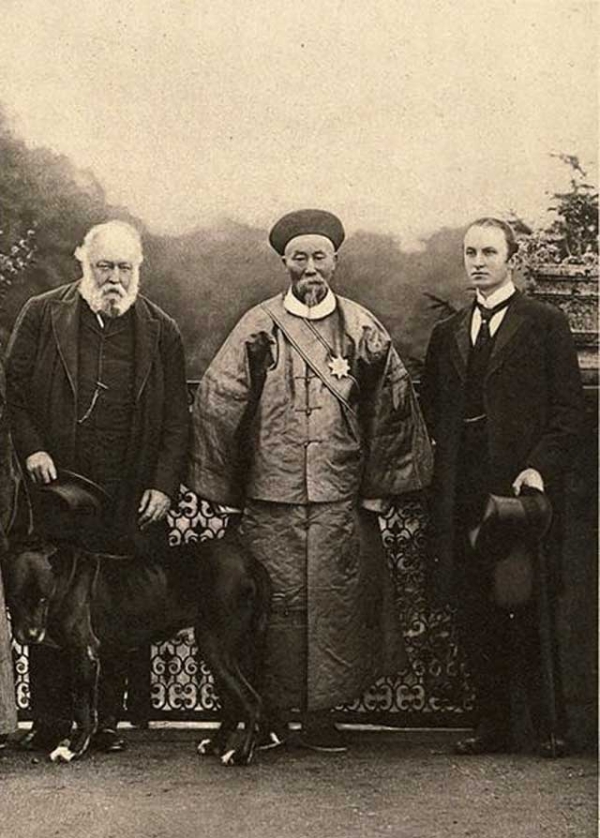

When the emperor died in 1861, Cixi’s five-year-old son became the Tongzhi emperor. In 1856 she rose steeply in rank after giving birth to the first (and as it happened only) male heir to the throne. If Chang is to be believed, Cixi should be considered a transformative figure in modern Chinese history, perhaps on the level of Mao Zedong, certainly the equal of Sun Yatsen or Chiang Kaishek.Ĭixi, the daughter of an unremarkable Manchu official, was chosen for the harem of the Xianfeng emperor of the Qing dynasty in 1852. Cixi also ‘championed women’s liberation’, and did it all ‘without … violence and with relatively little upheaval’. Under her leadership, we are told, major technologies were introduced, medicine improved, military industrialisation undertaken and a free press encouraged. Cixi ‘brought medieval China into the modern age’. ‘Empress Dowager Cixi’s legacy was manifold and towering,’ she writes. Jung Chang does not merely repeat what are now truisms in the representation of Cixi – that she has been obscured by misogyny and orientalist stereotyping, as well as the anti-Manchu sentiment running through Chinese nationalist narratives – but also claims to have discovered something new. Since Sterling Seagrave’s Dragon Lady of 1992, Cixi has been the subject of or a major figure in a dozen books, as well as films and television series.

And now she appears in the vanguard of stubborn Chinese opposition to foreign arrogance and encroachment.

In the 1960s and 1970s, she was one of a small collection of ‘powerful’ women newly discovered in Chinese history. In the first decade of the 20th century, she was either the vivacious tea hostess who had protected foreigners from Boxer mobs, or the murderous xenophobe who had set the rioters on them in the first place. E mpress Dowager Cixi of the Qing dynasty is one of those historical figures who are renovated from time to time as the moment demands.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)